Barrington, Illinois

Barrington, Illinois | |

|---|---|

Downtown Barrington | |

| Motto: "Be Inspired"[1] | |

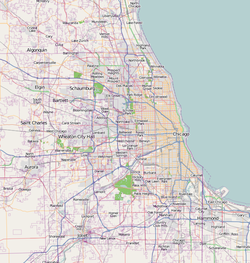

Location of Barrington in Cook and Lake counties, Illinois. | |

| Coordinates: 42°9′13″N 88°7′55″W / 42.15361°N 88.13194°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Illinois |

| County | Lake, Cook |

| Township | Barrington, Palatine, Cuba, Ela |

| Founded | 1865 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Village |

| • President | Karen Darch |

| Area | |

• Total | 4.79 sq mi (12.41 km2) |

| • Land | 4.61 sq mi (11.93 km2) |

| • Water | 0.19 sq mi (0.48 km2) |

| Elevation | 830 ft (250 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 10,722 |

| • Density | 2,327.33/sq mi (898.50/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 60010, 60011 |

| Area codes | 847, 224 |

| FIPS code | 17-03844 |

| Wikimedia Commons | Barrington, Illinois |

| Website | www |

Barrington is a village in Cook and Lake counties in the U.S. state of Illinois. The population was 10,722 at the 2020 census.[3] A northwest suburb of Chicago, the area features wetlands, forest preserves, parks, and horse trails in a country-suburban setting. Barrington is part of the Chicago metropolitan area.

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]The original settlers of the Barrington area were the indigenous peoples of the Native American Prairie Potawatomi or Mascoutin tribes, which later divided into the Potawatomi, Ojibwe, and Ottawa tribes.[4] Many local roads still in use today, including Algonquin Road, Rand Road, Higgins Road, and St. Charles Road, were originally Native American trails.[4] For many years, Barrington was considered part of the Northwest Territory, then the Illinois Territory.[5]

19th century

[edit]By treaty dated September 26, 1833, ending the Black Hawk War, the Ojibwe, Ottawa and Potawatomi tribes ceded to the United States all lands from the west shore of Lake Michigan west to the area that the Winnebago tribe ceded in 1832, north to the area that the Menominees had previously ceded to the United States, and south to the area previously ceded by an 1829 treaty at Prairie du Chien, a total of approximately 5,000,000 acres (20,000 km2).[6] Through this treaty, the Sauk, Meskwaki, Winnebago, Ojibwe, Ottawa and Pottawatomi tribes ceded all title to the area east of the Mississippi River. Between 1833 and 1835, the U.S. government paid approximately $100,000 in annuities and grants to the Potawatomi, Ottawa, and Ojibwe tribes, presumably as payment for the land.[6]

Following this treaty, pioneers traveled from Troy, New York, via Fort Dearborn (now the city of Chicago) to live in Cuba Township in Lake County.[7][8] The first white pioneers known to have settled in Barrington township were Jesse F. Miller and William Van Orsdal of Steuben County, New York, who arrived in 1834, before the three-year period which had been given the Native Americans to vacate the region, and before local land surveys.[9] Other Yankee settlers from Vermont and New York settled in what is now the northwest corner of Cook County.[7][8]

The combined settlement of these pioneers, located at the intersection of Illinois Route 68 and Sutton Road, was originally called Miller Grove due to the number of families with that surname[10] but later renamed Barrington Center[8][11] because it "centered" both ways from the present Sutton Road and from Algonquin and Higgins roads.[9] Although residents and historians agree that the name Barrington was taken from Great Barrington in Berkshire County, Massachusetts,[7] and that many settlers immigrated to the area from Berkshire County, there is currently no evidence that settlers emigrated from Great Barrington itself.[10] In addition, several original settlers, including Miller, Van Orsdal, and John W. Seymour, emigrated from Steuben County, New York,[6] which also features a town named Barrington founded in 1822. However, it is currently unknown whether any settlers emigrated from Barrington, New York, itself or whether the New York settlement influenced the naming of Barrington, Illinois.

Much of the history of Barrington since its settlement parallels the development of railroad lines from the port facilities in Chicago. In 1854, the Chicago and North Western Transportation Company, now known as the Union Pacific Northwest Line, led by William Butler Ogden, extended the train line to the northwest corner of Cook County and built a station named Deer Grove.[7]

In 1854, Robert Campbell, a civil engineer who worked for the railroad, purchased a farm 2 miles (3 km) northwest of the Deer Grove station and platted a community on the property.[7][8] Deer Grove residents protested, and at Campbell's request, the railroad later moved the Deer Grove station near its current location, which Campbell named Barrington after Barrington Center.[7][8] In 1855, the village's first lumber facility began operations on Franklin Street.[8]

By 1863, population growth during the Civil War era increased the number of Barrington residents to 300. In order to provide a tax mechanism to finance improvements, Barrington submitted its request for incorporation in 1863.[8] Delays due to the Civil War resulted in the appropriate incorporation deeds not returning to Barrington for nearly two years.[12] The Illinois legislature granted Barrington's charter on February 16, 1865.[7][12] The Village held its first Board meeting on March 20, 1865, and appointed resident Homer Wilmarth as Mayor for one year.[7][12]

In 1866, resident Milius B. McIntosh became the first elected Village President.[12]

In 1889, the Elgin, Joliet and Eastern Railway (the "EJ&E") was built through Barrington, crossing what is now the Union Pacific/Northwest Line northwest of town.[7] In the late 19th century, a series of fires damaged numerous downtown buildings. In 1890, fire swept along the north side of East Main Street east of what is now the Union Pacific/Northwest Line, destroying several buildings.[12] In 1893, another fire destroyed most of the block that is now Park Avenue, and in 1898 a fire destroyed several buildings along the north side of Main Street from Hough Street to the Northwest Line railroad tracks.[12] As a result of these fires, residents replaced the burned frame structures with more substantial brick and stone buildings, many of which remain in use today (albeit with substantially altered facades).[12]

20th century

[edit]

At the beginning of the 20th century, the village streets were unpaved, although the downtown area had wooden slat sidewalks, with some on elevated platforms.[12] The downtown area also featured hitching posts for tethering horses as well as public outhouses.[12] Meanwhile, fenced residential backyards in the village often contained livestock and barnyard animals.[12]

In 1907, the village began replacing its wooden sidewalks with cement pavement.[12] In 1929, the Jewel Tea Company built a new office, warehouse, and coffee roasting facility northeast of the village center, creating hundreds of local jobs despite the Great Depression.[13]

The last major fire in downtown Barrington occurred on December 19, 1989. The fire completely destroyed Lipofsky's Department Store, then one of the oldest continually operating businesses in the village.[12]

The Battle of Barrington

[edit]On November 27, 1934, a running gun battle between FBI agents and Public Enemy # 1 Baby Face Nelson took place in Barrington, resulting in the deaths of Special Agent Herman "Ed" Hollis and Inspector Samuel P. Cowley.[14] Nelson, though shot nine times, escaped the gunfight in Hollis's car with his wife, Helen Gillis. Nelson succumbed from his wounds at approximately 8 p.m. that evening and was unceremoniously dumped near a cemetery in Niles Center (now Skokie), Illinois.[15] Infamous for allegedly killing more federal agents than any other individual, Nelson was later buried at Saint Joseph Cemetery in River Grove, Illinois. A plaque near the entrance to Langendorf Park, part of the Barrington Park District, commemorates the agents killed in the gunfight.

21st century

[edit]In April 2009, in a non-binding referendum, residents voted in favor of permitting Barrington Township officials to begin looking into seceding from Cook County in part due to Cook County's increased sales tax,[16] now the highest in the country.[17] (See Government section below.) Today, Barrington and its nearby villages are considered to be some of the wealthiest in the country.[7]

Opposition to Canadian National Railway Purchase of EJ&E Railway

[edit]Since 2008, Barrington has made national news for its opposition to the purchase of the EJ&E by Canadian National Railway, known as "CN", a purchase that may drastically increase the number of freight trains passing through the village daily.[18][19] The EJ&E intersects at grade with eight major roads in the Barrington area, including Northwest Highway, Illinois State Route 59 and Lake Cook Road in downtown Barrington, as well as the Metra Union Pacific line.[20] By 2012, CN is expected to run at least 20 trains on the line per day.[20] In summer 2008, Barack Obama, then a U.S. senator for Illinois, voiced opposition to the purchase, vowing to work with affected communities to make sure their views were considered.[20]

On October 15, 2010, the CN railroad crossing at U.S. Route 14, as well as rail crossings at Lake Zurich Road and Cuba Road, were blocked for over one and half hours during the early afternoon rush hour due to a stopped 133-car CN southeast bound freight train.[20] At times during the incident, the Hough Street crossing was also blocked.[20] The stopped train also caused back-ups on the Metra commuter rail service of their "Union Pacific Northwest Line", which operates over Union Pacific's Harvard and McHenry subdivisions.[20] That same day, U.S. Rep. Melissa Bean (D-8th) and U.S. Senator Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) released a statement that Barrington will receive a $2.8 million grant to fund the planning, design and engineering of a grade separation at the U.S. Route 14 and CN railroad crossing.[20] Construction of any grade separation at that intersection is estimated to cost approximately $69 million; the source(s) of any such funding are currently unknown, and there are currently no plans to design or construct grade separations at any of the other seven Barrington area CN railroad crossings.[20]

Geography

[edit]According to the 2021 census gazetteer files, Barrington has a total area of 4.79 square miles (12.41 km2), of which 4.61 square miles (11.94 km2) (or 96.12%) is land and 0.19 square miles (0.49 km2) (or 3.88%) is water.[21]

Barrington is 30 miles (48 km) northwest of Chicago.[22]

Climate

[edit]Barrington has a continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfa), with summers generally wetter than the winters:

| Climate data for Barrington, Illinois (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1962–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 62 (17) |

69 (21) |

84 (29) |

89 (32) |

93 (34) |

102 (39) |

103 (39) |

100 (38) |

96 (36) |

88 (31) |

75 (24) |

67 (19) |

103 (39) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 28.7 (−1.8) |

32.8 (0.4) |

44.5 (6.9) |

57.5 (14.2) |

68.5 (20.3) |

77.5 (25.3) |

81.3 (27.4) |

79.2 (26.2) |

72.4 (22.4) |

60.1 (15.6) |

46.3 (7.9) |

34.2 (1.2) |

56.9 (13.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 21.1 (−6.1) |

24.6 (−4.1) |

35.5 (1.9) |

47.3 (8.5) |

58.4 (14.7) |

67.8 (19.9) |

72.0 (22.2) |

70.2 (21.2) |

63.0 (17.2) |

50.8 (10.4) |

38.2 (3.4) |

27.0 (−2.8) |

48.0 (8.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 13.4 (−10.3) |

16.4 (−8.7) |

26.5 (−3.1) |

37.2 (2.9) |

48.3 (9.1) |

58.1 (14.5) |

62.6 (17.0) |

61.2 (16.2) |

53.6 (12.0) |

41.5 (5.3) |

30.2 (−1.0) |

19.7 (−6.8) |

39.1 (3.9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −28 (−33) |

−26 (−32) |

−9 (−23) |

5 (−15) |

22 (−6) |

30 (−1) |

38 (3) |

38 (3) |

25 (−4) |

14 (−10) |

−10 (−23) |

−20 (−29) |

−28 (−33) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.07 (53) |

1.90 (48) |

2.35 (60) |

3.95 (100) |

5.15 (131) |

4.60 (117) |

4.02 (102) |

4.58 (116) |

3.65 (93) |

3.39 (86) |

2.58 (66) |

2.19 (56) |

40.43 (1,027) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 12.6 (32) |

8.5 (22) |

4.6 (12) |

1.1 (2.8) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

2.0 (5.1) |

9.6 (24) |

38.5 (98) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.2 | 8.6 | 10.0 | 12.6 | 13.8 | 12.7 | 9.8 | 10.9 | 9.6 | 11.3 | 10.6 | 10.9 | 131.0 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 7.3 | 5.8 | 3.2 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.5 | 6.4 | 24.9 |

| Source: NOAA[23][24] | |||||||||||||

The highest recorded temperature was 103 °F (39 °C) on July 10, 1974; the lowest recorded temperature was −28 °F (−33 °C) on January 31, 2019.[23] Historical tornado activity for the Barrington area is slightly below Illinois state average. On April 11, 1965, an F4 tornado approximately 9.4 miles (15.1 km) away from downtown Barrington killed 6 people and injured 75; on April 21, 1967, another F4 tornado approximately 5.1 miles (8.2 km) away from the village center killed one person, injured approximately 100 people and caused hundreds of thousands of dollars in damage.

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 410 | — | |

| 1890 | 848 | 106.8% | |

| 1900 | 1,162 | 37.0% | |

| 1910 | 1,444 | 24.3% | |

| 1920 | 1,743 | 20.7% | |

| 1930 | 3,213 | 84.3% | |

| 1940 | 3,560 | 10.8% | |

| 1950 | 4,209 | 18.2% | |

| 1960 | 5,434 | 29.1% | |

| 1970 | 8,581 | 57.9% | |

| 1980 | 9,029 | 5.2% | |

| 1990 | 9,504 | 5.3% | |

| 2000 | 10,168 | 7.0% | |

| 2010 | 10,327 | 1.6% | |

| 2020 | 10,722 | 3.8% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[25] | |||

| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[26] | Pop 2010[27] | Pop 2020[28] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 9,570 | 9,232 | 8,926 | 94.12% | 89.40% | 83.25% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 63 | 96 | 117 | 0.62% | 0.93% | 1.09% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 10 | 14 | 8 | 0.10% | 0.14% | 0.07% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 203 | 378 | 643 | 2.00% | 3.66% | 6.00% |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Other race alone (NH) | 11 | 7 | 12 | 0.11% | 0.07% | 0.11% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | 74 | 132 | 365 | 0.73% | 1.28% | 3.40% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 237 | 468 | 651 | 2.33% | 4.53% | 6.07% |

| Total | 10,168 | 10,327 | 10,722 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

As of the 2020 census[29] there were 10,722 people, 3,988 households, and 2,902 families residing in the village. The population density was 2,237.01 inhabitants per square mile (863.71/km2). There were 4,394 housing units at an average density of 916.75 per square mile (353.96/km2). The racial makeup of the village (including Hispanics in the racial counts) was 84.29% White, 6.02% Asian, 1.15% African American, 0.29% Native American, 2.11% from other races, and 6.15% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 6.07% of the population.

There were 3,988 households, out of which 38.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 60.41% were married couples living together, 11.36% had a female householder with no husband present, and 27.23% were non-families. 25.68% of all households were made up of individuals, and 13.47% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.09 and the average family size was 2.56.

The village's age distribution consisted of 26.9% under the age of 18, 4.9% from 18 to 24, 23.7% from 25 to 44, 24.4% from 45 to 64, and 20.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 40.8 years. For every 100 females, there were 84.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 78.9 males.

The median income for a household in the village was $112,794, and the median income for a family was $157,083. Males had a median income of $104,050 versus $61,388 for females. The per capita income for the village was $64,507. About 2.0% of families and 3.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 0.2% of those under age 18 and 13.0% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

[edit]

Barrington receives much of its sales tax revenue from its half-dozen car dealerships.[20] State sales tax figures indicate that Barrington's auto sales, gasoline sales and state-taxable auto repairs accounted for $2.1 million in sales taxes for the village in 2008, or approximately 56 percent of its sales-tax income.[20]

The Gatorade Sports Science Institute, often featured in the company's commercials, was formerly located in Barrington just west of downtown, across the street from Barrington High School before closing in June 2022.[30] Barrington was also formerly home to GE Healthcare IT prior to relocating to Chicago in 2016.[31] Other notable businesses include defense contractor ISR Systems, part of the Goodrich Corporation (formerly known as Recon Optical),[32] and commercial real estate developer GK Development. For many years, the village was home to the Jewel Tea Company;[33] its former headquarters was razed in the early 21st century for redevelopment as Citizens Park.[34]

In addition to its downtown area, the village is home to several shopping centers, including the Ice House Mall and The Foundry, located northwest of town.

Top employers

[edit]According to Barrington's 2018 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[35] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Barrington Community Unit School District #220 | 1,200 |

| 2 | Barrington Park District | 379 |

| 3 | Motor Werks of Barrington | 355 |

| 4 | The Garlands of Barrington | 295 |

| 5 | PepsiCo (Quaker Oats) | 287 |

| 6 | Barrington Transportation | 230 |

| 7 | Pepper Construction | 226 |

| 8 | Jewel Food Store | 190 |

| 9 | Wickstrom Ford | 176 |

| 10 | Heinen's | 142 |

Arts and culture

[edit]Annual celebrations and events in Barrington include the Memorial Day parade, a Fourth of July parade and evening fireworks display, and a Homecoming parade associated with Barrington High School. In addition, the village hosts the "Great Taste Fest of Barrington", a food festival exhibiting fare from local restaurants.[20] During the fourth weekend of every September, Advocate Good Shepherd Hospital hosts "Art in the Barn", a juried fine arts show that features the exhibition and sale of fine art.[36] Started in 1974 with only 30 artists, the event now attracts over 6,500 visitors and features live entertainment and pony rides for children in addition to the art exhibits.[36] A fundraising event, Art in the Barn has generated more than $2.5 million for Good Shepherd Hospital.[36] During May Barrington also hosts "KidFest Kite Fly" event which is free, fun, family event that gets the entire family outside and moving.

Barrington also hosts a variety of charity functions, including Barrington CROP Hunger Walk;[20] Relay for Life by the American Cancer Society held at Barrington High School;[37] and the Duck Race and Pool Party, a rubber duck race held to benefit JourneyCare (formerly Hospice and Palliative Care of Northeastern Illinois).[38]

Library

[edit]

The Barrington Area Library, located northeast of the village's center on Northwest Highway, contains over 226,000 book volumes and 27,000 audiovisual items.[39] Originally established in 1915, the library moved to its current site in the mid-1970s.[40] Through various additions, most recently in 1993, the building was expanded to its current size of approximately 60,000 square feet (5,600 m2).[40] The library currently features exhibits by local artists, including an outdoor sculpture garden.[41]

Architecture

[edit]

The Village of Barrington Historic District was established in 2001 to protect and preserve historical areas of the Village and individual structures and sites within this area which have historic, architectural or cultural significance.[42] Barrington's Historic Preservation Overlay District is noted for its Victorian, Victorian Gothic, Queen Anne, and other popular late-19th century forms of architecture.[43] Among Barrington's notable buildings is the Octagon House, also known as the Hawley House. Claimed to be built around 1860, although the oldest home in Barrington Village is on North Avenue dating to 1872, the Octagon House is listed on the National Register of Historic Places;[44] although initially a residence, it now serves as a commercial property.

The downtown area is home to the historic Catlow Theater, which features interiors by noted Prairie School sculptor and designer Alfonso Iannelli.[45] In May 1927, the Catlow Theater opened for business with Slide, Kelly, Slide as its first feature film. The Catlow is also listed on the National Register of Historic Places and continues to operate as one of the few remaining single-screen theaters in the area. The Catlow was one of the first theaters to offer in-theater dining, provided by the adjoining Showtime Eatery. Patrons may bring food from Showtime Eatery (formerly Boloney's) into the 526-seat auditorium.[46]

Another historic building in the village, the Ice House Mall, is located just northwest of the town's center. Originally built in 1904 for the Bowman Dairy, the brick structure, with its turn of the 20th century styling, served as an actual ice house for 68 years.[47] Renovations and additions beginning in the 1970s have transformed the original building into a collection of local specialty shops.

The Michael Bay 2010 re-make of A Nightmare on Elm Street was partially filmed in Barrington's Jewel Park subdivision (Built by the Jewel T company for their executives) using a home actually on Elm Street, using the village's residential architecture as a backdrop.[48]

South Barrington has been described as the, “9th circle of McMansion Hell” by local architectural critic, Kate Wagner, on architecture humor website McMansion Hell due to the high number of properties whose extremely large square footage and dubious architectural merits subjectively classify them as McMansions.[49]

Parks and recreation

[edit]The Barrington area features numerous parks and nature preserves. The Arbor Day Foundation has recognized Barrington as a Tree City USA every year since 1986, in part due to the village's Tree Preservation and Management Ordinance governing the proper care for trees within the area.[50][51] The Barrington Park District administers several Barrington area parks including Citizens Park, Langendorf Park (formerly North Park), Miller Park (formerly East Park), and Ron Beese Park( formerly South Park). Langendorf Park features tennis courts, playgrounds, outdoor and indoor basketball courts, baseball fields, meeting/activity rooms, and "Aqualusion", a water park that includes a zero-depth pool, lap pool, and diving area, and a splashpad. Northeast of town is Cuba Marsh Forest Preserve,[52] a 782-acre (3.16 km2) wetlands preserve featuring 3 miles (5 km) of crushed-gravel trail offering views of the adjacent marsh. The preserve is named for Cuba Road, which provides the park's northern boundary.[52] It is administered by Lake County Forest Preserves. In 2011, Barrington received a $65,000 grant from the Northwest Municipal Conference for preliminary engineering of a bike path along Northwest Highway.[20] However, a timetable for the project has not yet been set.[20]

There are two golf courses within village limits including the Makray Memorial Golf Club. (formerly known as the Thunderbird Golf Course)[53] Located southeast of the village center on Northwest Highway, the 18-hole course totals 7,000 yards (6,400 m) and includes four sets of tees per hole.[53] The other golf course is a five-hole public course operated by the Barrington Park District at the far western end of Langendorf Park.

Government

[edit]

The Village of Barrington is a home rule municipality which functions under the council-manager form of government with a village President and a six-member board of trustees, all of whom are elected at large to staggered four-year terms.[54][55] The current Village President is Karen Darch.[56] There are six current members of the Board of Trustees[56][57] in addition to a village treasurer.[56] The village clerk, also an elected position, is responsible for taking and transcribing minutes of all Village Board and Committee of the Whole meetings along with other municipal clerk duties.[54] The current village clerk is Adam Frazier, and the deputy village clerk is Melanie Marcordes.[56][57] A village manager currently Jeff Lawler [58][59] assist the President with local operations and projects.[60]

| Name[57] | Title[54][56][59] | Term Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Karen Darch | Village President | First elected April 2005, re-elected 2009, 2013, 2017, and 2021[61] |

| Jason Lohmeyer | Village Trustee | Re-elected April 2019[62] |

| Todd Sholeen | Village Trustee | Elected April 2017[62] |

| Jennifer Wondrasek | Village Trustee | Elected April 2017[62] |

| Kate Duncan | Village Trustee | Elected April 2019[62] |

| Emily Young | Village Trustee | Elected April 2019[62] |

| Mike Moran | Village Trustee | Appointed April 2019[62] |

| Tony Ciganek | Village Clerk | Re-elected April 2019 [62] |

| Scott Anderson | Village Manager[58] | Appointed by Village Board |

Relationship with Cook County

[edit]In April 2009, in a non-binding referendum, village residents voted in favor of permitting Barrington township officials to begin looking into seceding from Cook County.[16][63] The referendum, entitled "Barrington Twp – Disconnect from Cook County," asked, "Should Barrington Township consider disconnection from Cook County, Illinois, and forming a new county if a viable option exists for doing so?"[64] The referendum came in response to Cook County's increased sales tax, now the highest in the country, and increased tensions between the county and towns neighboring Lake County.[17][63] Hanover and Palatine townships, as well as the Village of Tinley Park, (already partially located in Will County,) also passed similar measures.[17][63]

Education

[edit]

Barrington serves as the geographic center for the 72-square-mile (190 km2) Barrington Community Unit School District 220. Schools located in Barrington include:[65]

- Barrington High School

- Barrington Middle School - Prairie Campus

- Barrington Middle School - Station Campus

- Arnett C. Lines Elementary School

- Countryside Elementary School

- Grove Avenue Elementary School

- Hough Street Elementary School (2015 Blue Ribbon school)[66]

- Roslyn Road Elementary School

St. Anne Catholic Community is a K-8 Catholic school.

Media

[edit]The Barrington Courier-Review is a local newspaper.[67]

Barrington is included in the Chicago market and receives its media from Chicago network affiliates. The Chicago Tribune and Chicago Sun-Times also cover area news. The village's Community Relations board broadcasts all Village Board meetings, as well as community announcements, on a local government-access television (GATV) cable TV station.[68]

Infrastructure

[edit]Transportation

[edit]Transit

[edit]Metra provides commuter rail service on the Union Pacific Northwest Line connecting Barrington station southeast to Ogilvie Transportation Center in Chicago and northwest to Harvard or McHenry.[69]

Highways

[edit] US Route 14 (Northwest Highway)

US Route 14 (Northwest Highway) Illinois Route 59 (Hough Street)

Illinois Route 59 (Hough Street) Illinois Route 68 (Dundee Road)

Illinois Route 68 (Dundee Road)

Medical and emergency

[edit]In 1927, residents established a "Barrington General Hospital" in a local house. The hospital closed in 1935.[20] Various resident petitions and fundraising during the 1960s and 1970s renewed interest in a local hospital, and Good Shepherd Hospital opened in 1979 north of Barrington.[20]

In 2009, the Barrington Police Department had 23 full-time police officers;[20] and in 2007, the Barrington Fire Department had 38 full-time firefighters. The Village has an emergency operations plan as well as a community notification system called Connect-CTY.[70]

Notable people

[edit]See also

[edit]

- The Battle of Barrington

- Barrington High School

- Catlow Theater

- Citizens for Conservation

- Elgin, Joliet and Eastern Railway

- Health World Inc.

- Jewel Tea Co.

- Lake Cook Road

- Octagon House

- Union Pacific/Northwest Line

- St. Anne Catholic Community

References

[edit]- ^ "Village of Barrington". Village of Barrington. Retrieved July 16, 2013.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

- ^ "Barrington village, Illinois". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- ^ a b Lines, Arnett C. "When the Indians Were Here". Barrington Area History. Barrington Area Library. Archived from the original on November 8, 2007. Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- ^ Lines, Arnett C. "In What Counties". Barrington Area History. Barrington Area Library. Archived from the original on November 8, 2007. Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- ^ a b c Lines, Arnett C. "Indian Defeats and Treaties". Barrington Area History. Barrington Area Library. Archived from the original on November 8, 2007. Retrieved May 1, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Barrington, IL". The Electronic Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago Historical Society. Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Barrington's History". Village of Barrington, Illinois. Village of Barrington. Archived from the original on September 20, 2011. Retrieved July 26, 2011.

- ^ a b Lines, Arnett C. "Settlement around Barrington Center". Barrington Area History. Barrington Area Library. Archived from the original on November 8, 2007. Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- ^ a b Lines, Arnett C. "Townships are Organized". Barrington Area History. Barrington Area Library. Archived from the original on November 8, 2007. Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- ^ "History of Barrington". Community Information. The Village of Barrington. Archived from the original on April 7, 2009. Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Village of Barrington. "Historic Places". Village of Barrington. Archived from the original on September 20, 2011. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ^ Blue, Renee. "Features". Qbarrington.com. Retrieved July 10, 2010. [dead link]

- ^ "The Officer Down Memorial Page Remembers ." Archived from the original on July 20, 2006. Retrieved December 13, 2006.

- ^ "Trace Outlaw Nelson on Death Ride." Chicago Tribune. November 29, 1934. p. 1

- ^ a b Tony A. Solano (April 8, 2009). "Abboud wins second term as president". Barrington Courier Review. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

Residents voted in favor of permitting township officials to begin looking into seceding from Cook County by a vote of 975 to 507 with 13 of 14 precincts reporting.

- ^ a b c Taliaferro, Tim (April 8, 2009). "Three Townships Vote To Secede From Cook County, But Will They?". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on April 12, 2009. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ Schaper, David (July 28, 2008). "Plan To Unsnarl Chicago Rail Hits Snags In Suburbs". Morning Edition. National Public Radio. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- ^ "Nimbyism in the Midwest – Train wreck in suburbia". The Economist. September 11, 2008. Retrieved May 7, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Chicago Suburbs News - Chicago Tribune". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- ^ "Gazetteer Files". Census.gov. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- ^ Lavelle, Marianne. "Illinois Village Leads Charge for Tougher Oil Train Rules. National Geographic. January 17, 2014. Retrieved on January 19, 2014.

- ^ a b "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Barrington 3SW, IL". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "P004 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Barrington village, Illinois". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, And Not Hispanic or Latino By Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Barrington village, Illinois". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, And Not Hispanic or Latino By Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Barrington village, Illinois". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ Schroeder, Eric (April 14, 2022). "PepsiCo to close Illinois R&D facility | Food Business News". www.foodbusinessnews.net. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 21, 2023.

- ^ "GE Healthcare-Testimonials -GE Healthcare Executive Team Biographies - Vishal Wanchoo". Gehealthcare.com. May 7, 2009. Archived from the original on May 21, 2011. Retrieved July 10, 2010.

- ^ "Customer Contact Guide". Goodrich.com. Archived from the original on July 27, 2010. Retrieved July 10, 2010.

- ^ "Jewel Tea Company Collectables". New Eastcoast Arms Collectors Associates, Inc. Archived from the original on April 16, 2009. Retrieved May 8, 2009.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2010. Retrieved April 24, 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Village of Barrington, Illinois Comprehensive Annual Financial Report" (PDF). May 25, 2019. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Events". Archived from the original on April 6, 2011. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

- ^ WebItMaster.com. "Relay For Life Of Barrington". Barrington Relay. Retrieved July 10, 2010.

- ^ "Village of Barrington - News". Ci.barrington.il.us. October 26, 2008. Archived from the original on January 19, 2010. Retrieved July 10, 2010.

- ^ "Barrington Community". Barrington Area Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on May 22, 2009. Retrieved May 8, 2009.

- ^ a b "History of the Barrington Area Library". Barrington Area Library. Archived from the original on August 24, 2007. Retrieved May 8, 2009.

- ^ "Sculpture Garden". Barrington Area Library. Retrieved July 10, 2010.

- ^ "Historic Overlay District".

- ^ See "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 25, 2011. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) for self-guided tour. - ^ "National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form" (PDF). HAARGIS Database. Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. Retrieved August 3, 2007.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Boloney's, Inc. "Catlow Theater History". thecatlow.com.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ Irv Leavitt (June 25, 2009). "A meal (or two or three) in a Catlow sandwich :: Food :: PIONEER PRESS :: Barrington Courier-Review". Pioneerlocal.com. Retrieved July 10, 2010.

- ^ "Mall History". Ice House Mall. Archived from the original on March 30, 2009. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ "Filming locations for A Nightmare on Elm Street". IMDb.com, Inc. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ "yet again we find ourselves in cook county". McMansionHell.com. June 10, 2022. Retrieved November 27, 2022.

- ^ "Tree Cities at". Arborday.org. Retrieved July 10, 2010.

- ^ http://www.ci.barrington.il.us/DocumentsAndForms/Tree%20Preservation%20%20Management%20Ord_060420.pdf[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "Cuba Marsh". Lake County Forest Preserves. Archived from the original on December 27, 2008. Retrieved May 8, 2009.

- ^ a b "Makray Memorial Golf Club". Makraygolf.com. June 8, 2004. Archived from the original on July 10, 2010. Retrieved July 10, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Village Board". Government. The Village of Barrington, Illinois. Archived from the original on March 9, 2009. Retrieved May 8, 2009.

- ^ "General Information". Community Information. The Village of Barrington, Illinois. Archived from the original on April 7, 2009. Retrieved May 8, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e "Elected & Appointed Officials". Contacts. The Village of Barrington, Illinois. Archived from the original on March 9, 2009. Retrieved May 8, 2009.

- ^ a b c "Village of Barrington, IL : Village Board". Archived from the original on September 5, 2011. Retrieved May 25, 2011.

- ^ a b "Lawler, Libit Promoted". Barrington Courier-Review. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- ^ a b "Staff Directory". Contacts. The Village of Barrington, Illinois. Archived from the original on March 9, 2009. Retrieved May 8, 2009.

- ^ "Village of Barrington Organization Chart". Government. The Village of Barrington, Illinois. Archived from the original on September 30, 2006. Retrieved May 8, 2009.

- ^ http://www.voterinfonet.com/abstract/040709.asp?cat_ID=1&race_nbr=18[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f g "Welcome to Barrington Il".

- ^ a b c [1] Archived April 11, 2009, at the Wayback Machine "Cook County secession: Townships vote selves out of Cook County," Chicago Tribune April 8, 2009. Retrieved 09-04-09.

- ^ "April 2009 Referenda". Cook County Clerk's Office. Archived from the original on April 9, 2009. Retrieved May 8, 2009.

- ^ "Barrington 220 Schools". Barrington 220 School District. Retrieved May 4, 2023.

- ^ U.S. Department of Education. "Blue Ribbon Schools, 2003–present" (PDF). ed.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved August 2, 2011.

- ^ "About Us reflects on the attractiveness of Barrington as a place to live". Qbarrington.com. Archived from the original on July 19, 2010. Retrieved July 10, 2010.

- ^ [2] Archived September 21, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "RTA System Map" (PDF). Retrieved January 30, 2024.

- ^ "Village of Barrington - Emergency Management". Ci.barrington.il.us. Archived from the original on July 6, 2010. Retrieved July 10, 2010.

Further reading

[edit]- Arnett C. Lines, "A History of Barrington, Illinois," 1977

- Diane P. Kostick, "Voices of Barrington," ISBN 978-0-7385-1980-7, Arcadia Publishing, 2002

- Pioneer Press, "A Day in the Life of Barrington,"[permanent dead link] retrieved July 30, 2009

- Cynthia Baker Sharp, "Tales of Old Barrington," 1976